The Bermondsey Horror: The Chilling Tale of Marie Manning and the Murder of Patrick O’Connor

Discover the dark story of Marie Manning, whose ambition led to the brutal murder of her lover, Patrick O’Connor, in 1849 London.

LONDONVICTORIAN LONDON

6/5/202510 min read

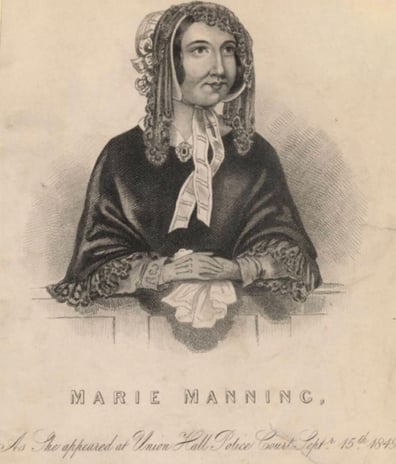

London, August 1849. A city suffocates under the dual oppressions of summer heat and the relentless grip of cholera. It is within this oppressive atmosphere that the chilling truth behind the disappearance of Patrick O'Connor, a well-to-do customs official, slowly begins to surface. At the heart of this macabre mystery lies Marie Manning, a woman of captivating beauty and cunning intellect, whose Swiss origins and French lilt mask a ruthless ambition.

Marie’s journey from a devout Swiss village to the labyrinthine streets of London is one of calculated survival and escalating deceit. Driven by a desire for a life of luxury, she marries Frederick Manning, a railway official who promises financial security but delivers only destitution and infidelity. Their shared dwelling at 3 Miniver Place in Bermondsey becomes the stage for a deadly charade. Patrick O'Connor, a former suitor whose comfortable fortune Marie covets, is lured into their home under the guise of friendship. As the days grow hotter and the city's anxieties mount, a sinister plot takes shape, meticulously orchestrated by Marie and reluctantly executed by Frederick.

The story delves into the psychological complexities of Marie, a woman who sees men as mere stepping stones to her desires, and Frederick, a weak-willed man trapped in a marriage of his own making, utterly dominated by his wife's sinister will. The narrative meticulously reconstructs the events leading up to O'Connor’s brutal murder and his subsequent burial beneath the very flagstones of the Manning’s kitchen. As the initial police investigation stumbles, it is the astute observations of a determined relative and the sharp eyes of an Edinburgh stockbroker that begin to unravel Marie's carefully constructed facade.

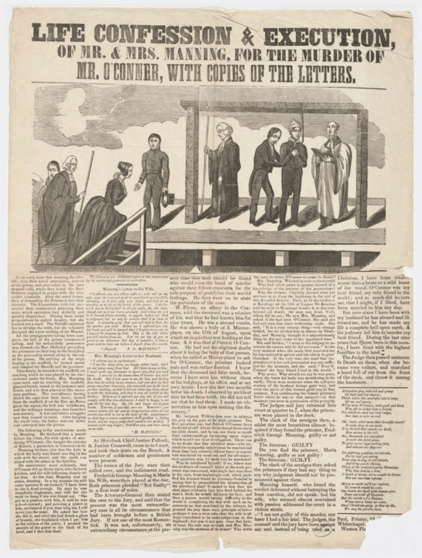

The manhunt intensifies, leading authorities across London and beyond, as Marie, ever the chameleon, attempts to escape with O'Connor’s stolen securities. Frederick, meanwhile, succumbs to the pressures of his guilt, his drunken confessions providing the crucial cracks in Marie’s seemingly impenetrable alibi. The subsequent trial, a spectacle that grips the nation, exposes the shocking depths of Marie’s depravity and challenges Victorian society’s preconceived notions of female criminality. The story culminates in a public execution, a grim spectacle witnessed by thousands, including the renowned Charles Dickens, leaving an indelible stain on London’s collective memory and cementing Marie Manning's legacy as a true "Lady Macbeth of Bermondsey."

Chapter 1: The Weight of Summer and a Woman’s Hunger

The summer of 1849 pressed down on London like a hot, damp blanket, suffocating. A greasy haze, thick with the exhalations of a million lives and the effluvium of a hundred thousand open sewers, clung to the very bricks of the buildings. The air in Bermondsey, where the Thames snaked its way past tanneries and wharves, was particularly foul, a rich stew of putrefaction and the metallic tang of damp earth, occasionally cut by the cloying sweetness of rotting fruit from the markets. Beyond the palpable discomfort, a more insidious menace stalked the labyrinthine alleys and crowded tenements: cholera. It was whispered in hushed tones over pint pots in dimly lit pubs like The Ship on Southwark Street, and spoken aloud in desperate prayers in overflowing churches, the tolling bells of St Mary Magdalen sounding a constant, mournful knell. Even the well-heeled, those who could afford the grand houses of Mayfair and the fresher air of Hampstead, felt its chilling breath upon their necks. No one was truly safe.

It was into this oppressive atmosphere that Patrick O'Connor, a man of fifty years with a comfortable paunch and an air of quiet respectability, vanished. He was an Irishman, originally, who had made his fortune as a gauger in the London Docks, a customs officer responsible for measuring alcohol for tax levies. He also dabbled, quite profitably, in moneylending, accumulating a considerable sum, largely in foreign railway bonds and shares, alongside a few hundred pounds in cash. His days were marked by the rustle of papers and the steady scratch of his pen at the custom house, a routine as predictable as the rising tide. When he failed to appear for work one sweltering Tuesday, his colleagues, accustomed to the city's prevailing sickness, assumed the worst – another victim succumbed to the dreaded disease. Three days later, when his absence became a prolonged and disturbing anomaly, the official report of a missing person was finally filed. The information provided to the constabulary was scant, yet chilling: Patrick O'Connor, last seen heading to dinner at the humble abode of a couple named Manning, at 3 Miniver Place, a small street off Weston Street in Bermondsey.

Miniver Place was not a grand thoroughfare. It was a narrow, unassuming lane, lined with modest two-up, two-down houses, their brick facades stained with soot and grime, facing the grittier back end of the Bermondsey Leather Market. The air here, though marginally better than the riverside, still carried the faint, sickly sweet scent of the nearby bone works, a constant reminder of the city's industrious, yet often grim, underbelly. When a lone constable, his heavy uniform sticking to his skin, knocked on the door of Number 3, he was met by a vision that seemed entirely out of place in such drab surroundings. The woman who answered was striking – dark-haired, with eyes that held an enigmatic glint, and a figure that bespoke an innate elegance. This was Mrs. Marie Manning, and her voice, when she spoke, carried a delightful, albeit pronounced, French lilt.

"Monsieur O'Connor?" she inquired, a faint, almost imperceptible tremor in her tone, "Ah, alas, he never arrived. I waited, and waited, but no. I have no idea where he could be." She gestured with a delicate hand towards the small, tidy parlour behind her, an unspoken invitation in her dark eyes. The constable, somewhat charmed despite himself, and inured to the casual disappearances of city life, thanked her politely and withdrew, his boots crunching on the grimy cobblestones. He had no reason to suspect the serene, beautiful woman who had just lied to his face.

But the seed of suspicion, once planted, has a curious way of rooting itself in the mind. A few days later, a persistent relative of O'Connor, a man whose quiet insistence bordered on obsession, managed to sway the police to revisit Miniver Place. By this time, handbills describing O'Connor and his disappearance were being circulated to all police stations in London. This time, however, there was no charming Marie to greet them. The house, when they knocked, echoed with a hollow silence. A faint, almost imperceptible smell of damp earth and something acrid hung in the air. The Mannings, it seemed, had vanished as completely as Patrick O'Connor himself.

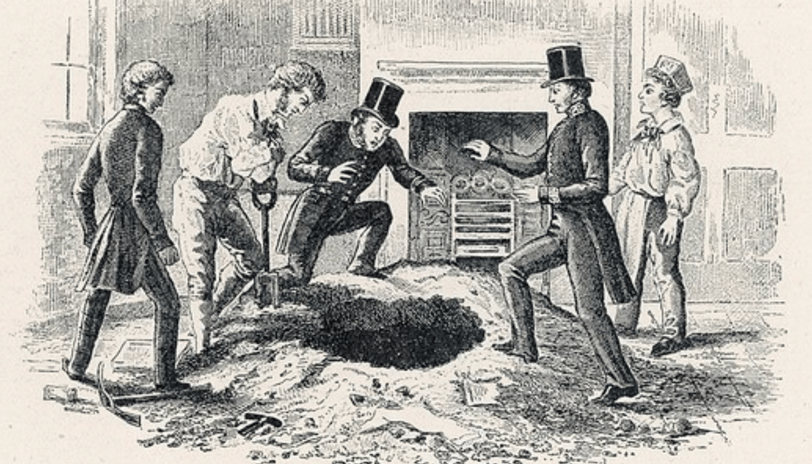

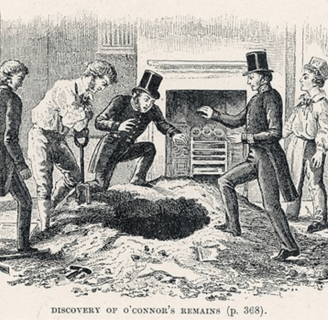

The police, now thoroughly intrigued, forced their way in. Constables Henry Barnes and James Burton led the search. Each room was searched with a methodical thoroughness, the silence broken only by the creak of floorboards and the occasional grunt of an officer. In the small, unadorned back kitchen in the basement, their attention was drawn to a peculiar detail: the flagstones, usually flush and firmly set, appeared to have been recently disturbed. A faint, almost imperceptible hairline crack ran along the mortar of two particular stones, and the earth beneath them seemed, just subtly, to have shifted. A chilling premonition, cold and sharp as a surgeon’s scalpel, descended upon the constables. With a grunt of effort, two officers began to pry at the stones. The scent of fresh earth, moist and raw, filled the confined space, mingling with the faint, cloying sweetness of something else, something far more sinister.

One of the officers, Constable Barnes, plunged his hand into the disturbed soil. He felt it before he saw it – a cold, unyielding object. "Good God," he muttered, withdrawing his hand, his face paling beneath the grime. "I… I felt a toe." They dug deeper, the shovels biting into the soil with a sickening scrape. What emerged from the depths of that kitchen floor would forever be etched into the minds of those who witnessed it. A man, fully naked, his body contorted in a grotesque fashion, his legs doubled up behind him and tied tightly at the hips with a clothesline. He lay on his stomach, his head buried slightly deeper in the ground, his face, or what remained of it, unrecognisable. Someone had poured unslaked lime over the corpse, a desperate, futile attempt to dissolve the evidence, its corrosive action having already "eaten away" flesh in several places. But the lime, while disfiguring, had not obliterated everything. From the gaping, toothless maw of the deceased, a set of false teeth protruded, a grim and undeniable identifier. The name, whispered with a mixture of horror and grim satisfaction, was Patrick O'Connor.

Chapter 2: The Serpent’s Path

Marie de Roux, as she was christened, entered the world some twenty-eight years prior in the Swiss city of Lausanne, nestled amidst the pristine, snow-capped peaks of the Alps. Her father, a man of profound piety and simple faith, harboured a fervent dream for his daughter: that she would dedicate her life to God, a nun shrouded in the quiet devotion of the convent. But Marie’s spirit was not one for quiet devotion. It bristled with an untamed ambition, a simmering discontent with the humble limitations of her birth. One crisp, mountain morning, under the vast, indifferent sky, she vanished, leaving behind the cloistered dreams of her father and eloping with an Italian bandit, a man whose wildness mirrored her own nascent desires for a life unbound by convention.

Their time in the Alpine shadows, a blur of illicit adventures and transient freedoms, eventually gave way to the lure of grander stages. Marie, ever the pragmatist, recognized the limited scope of a bandit’s life. She slipped away, making her way across the rugged terrain to France, where a new chapter, albeit a dishonest one, began. She secured a position as a lady’s maid to a transient Irish lady, a fleeting connection that served Marie’s opportunistic nature perfectly. It wasn't long before her mistress's valuables found their way into Marie's possession, a quiet, almost elegant pilfering that underscored her burgeoning talent for deception. With her ill-gotten gains, Marie set her sights on London, a sprawling metropolis that promised anonymity and, more importantly, opportunity.

In the bustling, cacophonous heart of London, Marie’s refined manners, a veneer of Swiss innocence polished with French sophistication, served her well. She secured employment initially as a maid to Lady Palk of Haldon House, Devon, before joining the service of Lady Blantyre at Stafford House, London, in 1846, a woman of considerable social standing. Here, Marie moved within circles that were far removed from the rustic simplicity of her childhood, observing, learning, and planning. Her dream, a persistent, glittering mirage, was to marry a man of substantial wealth, a gentleman who could offer her the life of ease and luxury she so desperately craved.

During her time in service, a world of potential suitors opened up before her. Two particularly caught her calculating eye. The first, Patrick O'Connor, was a man of considerable fortune, his pockets bulging with the fruits of his customs work and moneylending. He was known to have had a romantic relationship with Marie, yet he possessed a regrettable fondness for the bottle, a habit that, while perhaps endearing to some, Marie saw as a potential liability. The second, Frederick George Manning, a guard on the Great Western Railway, was closer to her own age, outwardly abstemious in his habits, and, crucially, boasted of a solid financial standing and an inheritance waiting in the wings from his mother. Frederick, a man whose background was already chequered by suspicions of involvement in railway robberies, was a plausible, if somewhat unstable, prospect.

Frederick, with his eager pronouncements of wealth and future prospects, proved to be the more pliable of the two. On May 27th, 1847, Marie, with a carefully crafted blend of allure and feigned vulnerability, ensnared him. They married at St James’s Church, Piccadilly, a union of convenience for Marie, a hopeful new beginning for Frederick. But the veneer of prosperity soon cracked. Frederick, it transpired, was a liar, his promises of wealth as empty as his pockets. He drank, albeit more discreetly than O'Connor, and his fidelity was as fleeting as a summer breeze. The gilded cage Marie had imagined dissolved into a drab reality of mounting debts and bitter disappointment. The simmering resentment within her festered, eventually blossoming into a cold, hard desire for revenge. Frederick had betrayed her trust, dashed her dreams, and for that, he would pay. Her initial acts of vengeance were small, petty thefts from his dwindling resources, a deliberate act of financial sabotage.

Despite her marriage, Marie continued her friendship with Patrick O'Connor. They remained in contact, and it was widely believed she was still having an affair with him, seemingly with Frederick's tacit acquiescence. Then came the seemingly innocuous proposition from Patrick O'Connor. He had, at Marie’s subtle urging, expressed an interest in becoming a lodger in their modest home on Miniver Place. For a fleeting moment, a glimmer of hope sparked within Marie – a way to salvage their precarious financial situation. But O'Connor, a man of unpredictable whims, abruptly changed his mind, opting instead for a quiet boarding house on Greenwood Street, Mile End Road. Marie’s fury was a silent, internal conflagration. She had manipulated, she had planned, and O'Connor had, unwittingly, thwarted her. He had no idea of the dark, malevolent seeds his innocent decision had sown in the fertile ground of Marie’s vengeful mind.

A new lodger arrived at Miniver Place, a young medical student named William Massey. He was a curious, earnest sort, eager to learn, and perhaps a little too trusting. Marie, ever the astute observer, began to subtly probe his knowledge. Her questions, seemingly casual, held a chilling undercurrent. "Tell me, Mr. Massey," she would inquire, her French accent lending a certain charm to the macabre subject, "what would be the most effective way to… dispatch someone, cleanly, swiftly?" And later, with a feigned philosophical air, "Do you believe, Mr. Massey, that murderers find their way to heaven?" Massey, oblivious to the true nature of her inquiries, would offer his medical insights, inadvertently providing Marie with the gruesome details she sought.

Despite their outward cordiality, a strange tension permeated the Manning household. Marie, ever the manipulator, maintained a facade of warm friendship with Patrick O'Connor, frequently visiting him at his new boarding house, her presence a silken thread weaving around his unsuspecting life. Then, in late July, Frederick, prompted by Marie, made a curious purchase: a sturdy crowbar. He accepted the delivery on the street, his usual feckless demeanor replaced by a nervous, almost furtive air. A few days later, a sack of unslaked lime, ostensibly for "pest control," arrived. Marie, however, greeted this particular delivery with a serene smile, a chillingly calm acceptance of the instrument of their impending doom.

The final pieces of Marie’s deadly puzzle were falling into place. The young medical student, William, was abruptly informed that he must find new lodgings, his innocent presence no longer serving Marie’s sinister purpose. On the evening of August 8th, Marie, her eyes glinting with a cold, determined resolve, extended another invitation to Patrick O'Connor. This time, however, the invitation came with a specific, chilling caveat: "Come to dinner, dear Patrick, but please, come alone." She had planned to kill him that night, but O'Connor, to her barely concealed frustration, arrived with a friend, thwarting her meticulously laid trap. Marie, quick-witted as always, feigned a pleasant evening, massaged his temples with perfume when he complained of a headache, and then, as he was about to leave, offered the same invitation for the following evening, stressing the intimacy of a solitary supper. The stage was set. The humid London air, heavy with the scent of unslaked lime and the unspoken dread of cholera, seemed to hold its breath.